Endless Forms Most Beautiful, a song cycle setting a selection of poems from Darwin’s Microscope and Guests of Time to music written by composer Cheryl Frances-Hoad, debuted at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History on 18th October 2019. Music: Carola Darwin, soprano, and Gildas Quartet.

Endless Forms Most Beautiful received 4 out of 5 stars in The Times, and was described, after a sold-out performance, as a “shrewd, witty, and imaginative song cycle”.

It had a sold-out performance in Cambridge at Kettle’s Yard, on 28th November 2019.

Darwin’s Microscope (Valley Press, 2019,) is available from Blackwell’s & Valley Press.

12 December, 2016: Guests of Time launch

Together, the poems in this anthology are a tribute to the Pre-Raphaelite origins of the Oxford University Museum, and a rejuvenation of its artistic legacy. Order your copy today.

6 October: On TV for National Poetry Day!

The past few months have been abuzz with poet-in-residence activity, both behind the scenes and ‘front of house’.

The past few months have been abuzz with poet-in-residence activity, both behind the scenes and ‘front of house’.

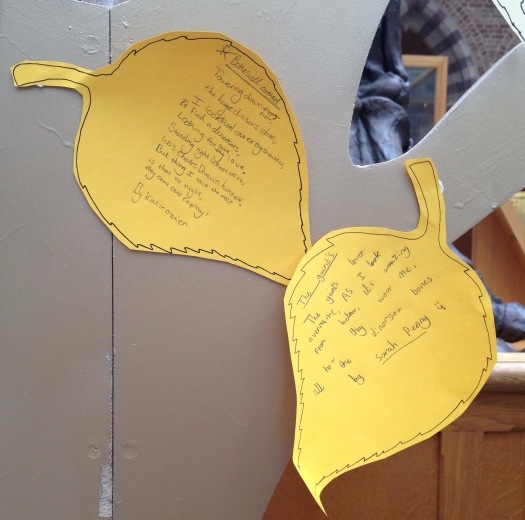

All three of us spent National Poetry Day in the Museum. We set up a Poetry Tree and Poetry Trail, which were taken up with enthusiasm by guests of all ages.

Each poet has a video online and on display in the foyer, where we read new work inspired by our residencies.

The full anthology, Guests of Time, will be launched at the Museum on 12 December. It is free, but sign up to the guest list in advance!

18 March: Entomology!

Thanks to Amo for her thorough introduction to the live specimens in Entomology. I’m completely smitten with the Orchid Mantis, whom Amo invited me to name. Decided on Daphne. She / it sat on my hand, seemed interested in my ring, and cleaned herself fastidiously…Then proceeded to grab a cricket and eat it (live, of course) head-first.

John Barnie and I also got to handle cockroaches (I held a Madagascan hissing cockroach) and to see the UV light given off by scorpions; to see the tarantulas, and hold several other mantid specimens. But Daphne takes the cake. (Or, to be more precise, the cricket.)

17 March: Exhibition and Archives

The first of three ‘phases’ for Visions of Nature is a special exhibition, ‘Bee (and the odd wasp) in my bonnet‘ by artist Kurt Jackson, an Oxford alum who reminisced about the bee specimens he brought back to the Museum as a student.

The first of three ‘phases’ for Visions of Nature is a special exhibition, ‘Bee (and the odd wasp) in my bonnet‘ by artist Kurt Jackson, an Oxford alum who reminisced about the bee specimens he brought back to the Museum as a student.

(The Director Paul wasn’t quite certain where, among the million-odd specimens in the collections, those bees had got to…)

The private view of the exhibition was a lovely evening, and it was particularly exciting to be in the Museum after hours. Champagne and speeches flowed, but the star of the evening was Kurt’s show, which has been beautifully displayed on the upper far gallery, overlooking the T-Rex. ‘Bee in my Bonnet’ is on until 29 September and well worth seeing.

If being one of the first to see the exhibition wasn’t enough of a treat, it was, in fact, a calmer point in my day. Earlier, poet John Barnie and I had been welcomed into the Archives by Kate Santry, who showed us original materials, some of which had become myths in my mind…

Honestly, I don’t know which was best. They are all amazing:

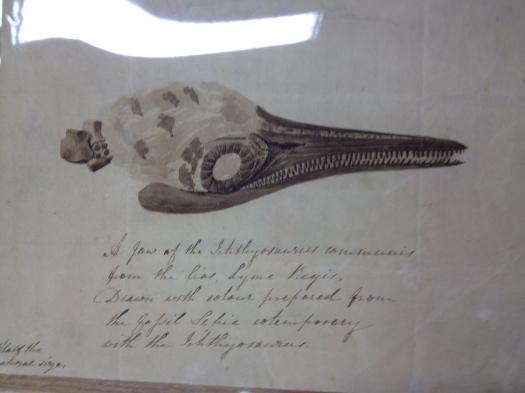

THE original Elizabeth Philpot painting, done using fossil squid ink, of an Ichthyosaurus, ‘from the Lias, Lyme Regis’.

THE original Elizabeth Philpot painting, done using fossil squid ink, of an Ichthyosaurus, ‘from the Lias, Lyme Regis’.

One of the original William Smith geological maps:

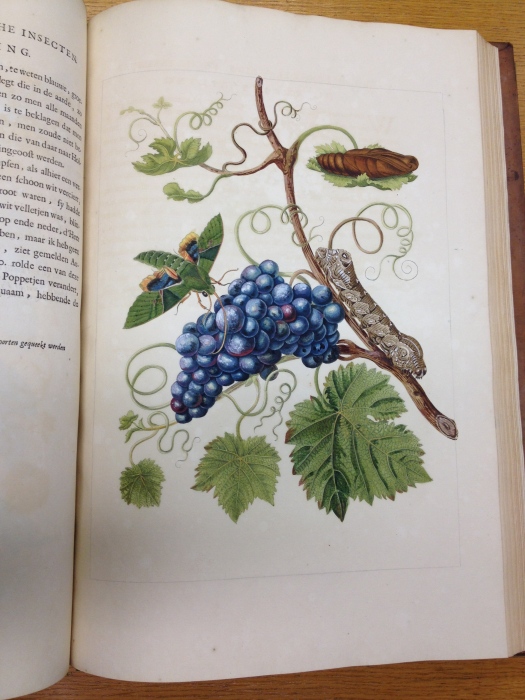

The astonishing hand-coloured ‘Insects of Surinam’ by Maria Sibylla Merian, Dutch naturalist and explorer extraordinaire. (She travelled to Surinam in 1699 with her daughter, and no men).

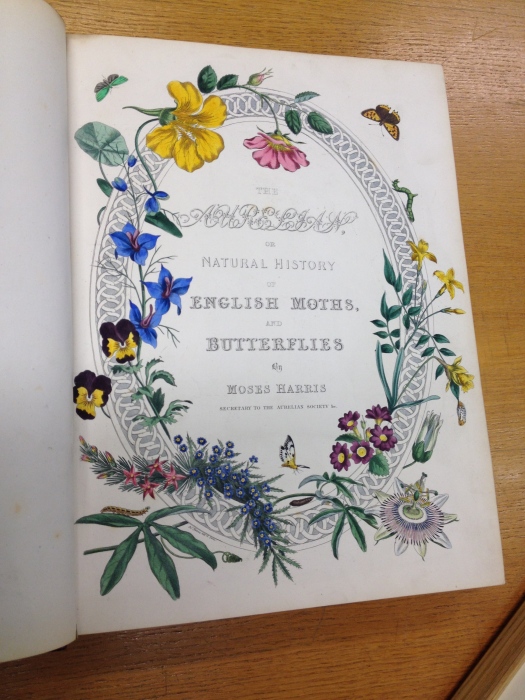

The Aurelian: As far as I can gather, this book is the basis for lepidopterists’ version of the Illuminati.

…Many, many thanks to Kate, for showing us these treasures.

The collections are open to anyone with a research interest.

12 Feb: Happy Darwin Day!

On the anniversary of Darwin’s birthday, I was fortunate enough to enjoy a spectacular behind-the-scenes orientation of the Museum.

This is thanks to the great generosity and enthusiasm of the curators, whom I had the pleasure to meet – honestly, curators are some of the best people in the world, not only ‘custodians of the future’, as Sarah from the Lyell Project put it, but also gatekeepers of the past and present, those whose warm welcome makes is essential when it comes to accessing materials, specimens, and knowledge itself.

First, I met Imran, who is working on fossil echinoderms, trying to understand why the five-branched symmetry of modern echinoderms (like starfish and sea cucumbers) became the dominant body type. Fossil echinoderms are found in a much more diverse array of shapes than modern ones, and Imran showed me some great 3-D printed fossil echinoderms, the shapes of which had been mapped straight out of fossil rock using CT Scanning.

First, I met Imran, who is working on fossil echinoderms, trying to understand why the five-branched symmetry of modern echinoderms (like starfish and sea cucumbers) became the dominant body type. Fossil echinoderms are found in a much more diverse array of shapes than modern ones, and Imran showed me some great 3-D printed fossil echinoderms, the shapes of which had been mapped straight out of fossil rock using CT Scanning.

Sarah collected me next, and showed me around the collections of Charles Lyell, whose ideas about how vast geologic time actually was were essential towards Darwin’s understanding of evolutionary change.

We were especially interested in some beautiful trails left along fossil shells, which Sarah is looking into – almost certainly the marks of some other creature predating on the snail. We talked about how marine biologists would surely have some ideas – possibly sponges or other shells leave marks of predation. It’s a great example of Sarah, a palaeontologist, reaching across specialisations to help her find answers in her own work.

We were especially interested in some beautiful trails left along fossil shells, which Sarah is looking into – almost certainly the marks of some other creature predating on the snail. We talked about how marine biologists would surely have some ideas – possibly sponges or other shells leave marks of predation. It’s a great example of Sarah, a palaeontologist, reaching across specialisations to help her find answers in her own work.

Next, Eliza, a palaeontologist, took me to see one of the most exciting creatures in the Museum – and also the newest! I got to meet Eve, the long-necked plesiosaur, a ‘vanishingly rare’ 165-million-year-old specimen which may prove to be an entirely new species. Eve isn’t even ‘finished’ yet – the bones are being carefully cleaned of mud and cemented sediment.

Eve’s body is in one room, whilst, in a workshop next door, her skull is being meticulously cleaned by preservator Juliet. It was especially fascinating to meet Juliet and ask her a few questions about what it was like to work on Eve – I would go into detail here, but am going to save it up for a poem, since that is, after all, my purpose at the Museum.

Eve’s body is in one room, whilst, in a workshop next door, her skull is being meticulously cleaned by preservator Juliet. It was especially fascinating to meet Juliet and ask her a few questions about what it was like to work on Eve – I would go into detail here, but am going to save it up for a poem, since that is, after all, my purpose at the Museum.

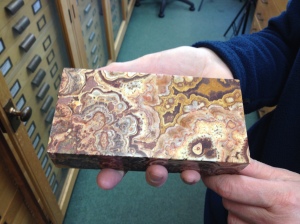

My next stop was to meet Monica in the geological collections – and though all the rest had been absolutely wonderful, I began to seriously lose track of time in here. Perhaps it was the feeling of the rooms; like a library with shelves and shelves, except instead of books, here are gorgeous minerals one can, if one knows the language, ‘read’…One of the most famous collections here is the Corsi Collection of Decorative Stones – heads-up to architects as well as geologists: 1,000 perfectly polished rectangular slabs of hand-sized stone from all over the world which allows researchers to do things like go to an auction house and identify exactly where that marble table-top came from. In this photo, Monica is holding a piece from Mt Vesuvius.

My next stop was to meet Monica in the geological collections – and though all the rest had been absolutely wonderful, I began to seriously lose track of time in here. Perhaps it was the feeling of the rooms; like a library with shelves and shelves, except instead of books, here are gorgeous minerals one can, if one knows the language, ‘read’…One of the most famous collections here is the Corsi Collection of Decorative Stones – heads-up to architects as well as geologists: 1,000 perfectly polished rectangular slabs of hand-sized stone from all over the world which allows researchers to do things like go to an auction house and identify exactly where that marble table-top came from. In this photo, Monica is holding a piece from Mt Vesuvius.

Because I recently wrote a piece for The Lancet Psychiatry on John Dee, I’ve been reminded of alchemy and the links between medicine and minerals. So I asked Monica about that, and she had time to show me some amazing little clay tablets that were used for medicinal purposes.

Because I recently wrote a piece for The Lancet Psychiatry on John Dee, I’ve been reminded of alchemy and the links between medicine and minerals. So I asked Monica about that, and she had time to show me some amazing little clay tablets that were used for medicinal purposes.

Next, I was swept off by Zoe of Entomology into some of the more grand rooms of the Museum, not least, the room in which the ‘great debate’ or ‘Huxley-Wilberforce Debate’ was held in 1860! Right now, the room also holds a huge part of the Museum’s entomology collections, and Zoe pulled out many drawers of gorgeous insects for me…it felt so special and dizzying in the number and variety of what I saw, but briefly, it included beetles, butterflies, and flies.

It was especially interesting to talk about collecting and conservation with Zoe, because I felt like the number of dead insects was overwhelming and it made me wonder how there are any butterflies left; Zoe helpfully pointed out that insects, with their huge numbers of offspring and short lifespans, have a much higher turnover rate than birds or mammals. Because of course, Victorian museum collections were responsible for devastating animal populations, whereas now the main purpose of museums and zoos is conservation.

It was especially interesting to talk about collecting and conservation with Zoe, because I felt like the number of dead insects was overwhelming and it made me wonder how there are any butterflies left; Zoe helpfully pointed out that insects, with their huge numbers of offspring and short lifespans, have a much higher turnover rate than birds or mammals. Because of course, Victorian museum collections were responsible for devastating animal populations, whereas now the main purpose of museums and zoos is conservation.

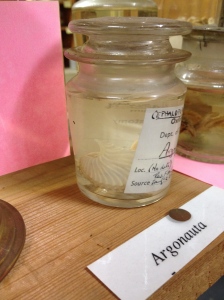

My last meeting on this brilliant whirlwind tour was with Mark of Zoology, who took me downstairs into the Spirit Stores. I was touched that all of the curators had taken note of my particular interest in cephalopods, so Mark took me straight to them – jar upon jar of preserved squids, cuttlefish, nautiluses and – I was hugely delighted to ask him to point out – the paper nautilus, or argonauta. My first reaction was – ‘they’re tiny!’ I had no idea! These are, for my money, the coolest creatures in the sea.

The argonaut is a pelagic octopus that secretes its ‘papery’ shell, which is a brood chamber for its young. So, unlike a nautilus or the fossil ammonite, this shell is not attached to the creature inside. They are beautiful and mysterious, and near impossible to keep in captivity, as they only thrive being buoyant in the open ocean. I am definitely going to write about the paper nautilus. Also, any argonaut you might see is a female: males rarely grow larger than 2cm; it took ages for biologists to understand the extreme sexual dimorphism in the species. They thought that argonauts frequently had a small parasite attached: it was, in fact, the male of the species.

The argonaut is a pelagic octopus that secretes its ‘papery’ shell, which is a brood chamber for its young. So, unlike a nautilus or the fossil ammonite, this shell is not attached to the creature inside. They are beautiful and mysterious, and near impossible to keep in captivity, as they only thrive being buoyant in the open ocean. I am definitely going to write about the paper nautilus. Also, any argonaut you might see is a female: males rarely grow larger than 2cm; it took ages for biologists to understand the extreme sexual dimorphism in the species. They thought that argonauts frequently had a small parasite attached: it was, in fact, the male of the species.

This is only a fraction of what I was able to see, and there is so much to mull over! My thanks to Ellie, Imran, Sarah, Eliza, Monica, Zoe, and Mark for this amazing day.

22 Jan: What a remarkable start to 2016 – being welcomed as one of three Poets-in-Residence at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History.

Along with poets John Barnie and Steven Matthews, I have the privilege of visiting the Museum regularly and exploring the collections, meeting the curators, and generally indulging in the magnificent natural history specimens, architecture, stories, and history that make up this marvellous Oxford institution.

As the year progresses, all the poets will write new work, which will culminate in an anthology, introduced by academic of science-and-literature, Professor John Holmes, whose energy and ideas were a major driving force behind this project. The poetry residencies are part of ‘Visions of Nature’, a year-long programme of events and exhibitions taking place throughout the Museum.

It was fitting that, as part of our introductory tour of the Museum, we were introduced to the original Oxford Dodo specimen – the only Dodo specimen to have soft tissue remains, and thus be useful for DNA analysis (sorry, but the Dodo is just a large pigeon – an example of island ‘gigantism’) – and probably the inspiration for the Dodo in Alice in Wonderland.